With the film Oppenheimer in the news, it’s important to understand the full context of the atomic destruction of two of Japan’s major cities.

A few years back I attended a poetry reading involving a friend of mine. To know her back story, being bundled off to England prior to the holocaust never to see her real parents again, adds a haunting dimension to her verses.

However, my friend was not the only one reading, so I stayed and listened to another woman’s tome about the horrors of Hiroshima.

I was of course disturbed by the vision of lives lost that day, but I was similarly staggered by her isolating the event as the premiere horror of the conflict.

Over the previous eight years of war, the Japanese killed, raped, and experimented on millions of human beings. Hiroshima and Nagasaki did not happen out of the blue.

Just minding our own business?

While I’ve never spent time in Japan, I have spent more than a few hours watching online tours of the country’s various WWII-related museums. There’s a curious disconnect, or more directly–avoidance of responsibility for Japan’s initiation of the conflict, and its military’s brutal behavior.

The museums almost seem to convey the idea that Japan, Hiroshima, and Nagasaki were just mozying along one day when a bomb destroyed a city. To an extent, and in terms of the average non-combatant, this might seem true–but its also an extremely naive and myopic perspective.

Given Japan’s behavior throughout the war, this omission and attitude seem strange to outsiders. The present generation, of course, isn’t at fault, but acknowledgement of the past should have come long ago from those involved.

There may be an undercurrent of the proper sentiment, but verifying that is beyond my pay grade. Put another way, I don’t understand the psychology involved.

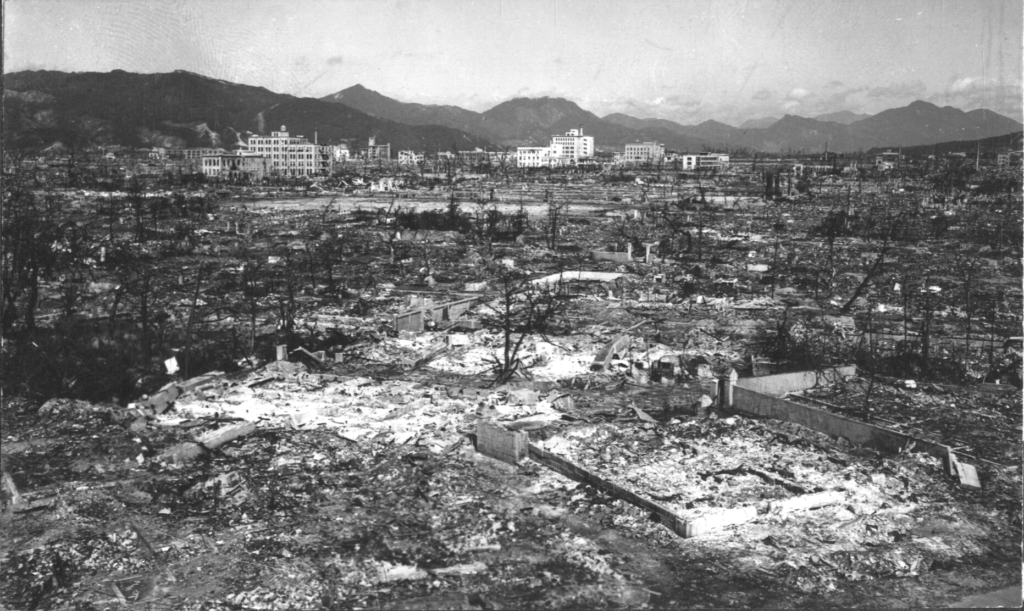

As previously stated, prior to the atomic bombings, Japanese troops had killed and enslaved millions of Chinese, Koreans and other peoples, as well as raped and pillaged wholesale. The above photo is from Nanking.

Medical “experimentation” occurred, and not on a small scale. Search “Unit 731”. To paraphrase one Japanese soldier who served in China and Nanking (modern Nanjing), “We were animals gone mad”.

Unfortunately, bad behavior was baked into the credo of the contemporary Japanese warrior. Many believed that dying for the Emperor was an honor, so the lives of others, especially those who had “shamed” themselves by surrendering, were not held in high regard. See the Battle of Manila.

The staggering cost of an invasion

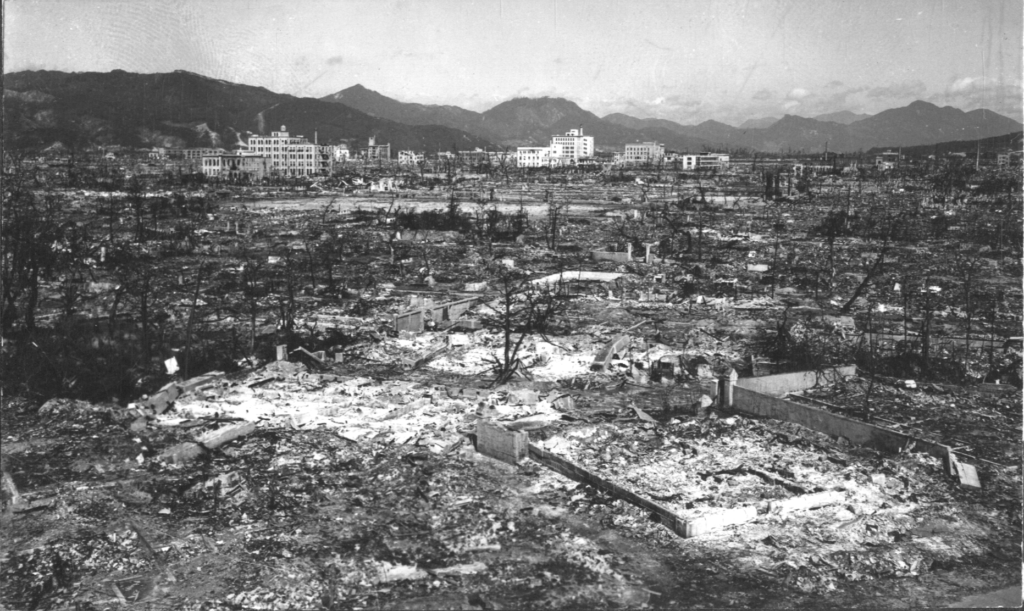

The atomic bombs took around 200,000 lives (one estimate), directly and indirectly. But that’s only half the equation. The other half hinges on Japan’s dogged determination to fight to the last man throughout the Pacific, and the enormous casualties experienced (military and civilian) at Okinawa.

Japan’s strategic intent, clearly stated during the latter stages of the Pacific campaign, was to make victory appear so costly to the enemy that they would never prosecute the war to its conclusion–the unconditional surrender and occupation of Japan.

Those late war experiences convinced just about every ally that an invasion of the Japanese home islands would be a bloodbath of monumental proportions, unprecedented during the Pacific war, though common on the eastern front (German vs. Russia, see Kursk).

Estimates for the human cost of invading Japan were placed at one million dead and wounded allied servicemen, and roughly ten times that in Japanese military personnel and civilians. (The Allies held overwhelming material and technical advantages.)

However, the Japanese strategy proved another ill-fated attempt to defeat the will of the enemy, a common mistake made throughout the 20th century and still seen today. They grossly underestimated the resolve of the United States and its allies from the beginning. The no-quarter nature of the combat didn’t help either. Forgiveness of any sort was not in the air.

While unconditional surrender was the allied aim, ultimately we unofficially let it be known that Japan could keep its emperor. This as a bone for dignity and for the sake of a calmer occupation. That unofficial promise was kept.

Other miserable alternatives

The U.S. Navy didn’t want to invade, but instead, proposed to blockade Japan while American air power destroyed everything of value. Including, no doubt, food stuffs and agricultural infrastructure. The number of U.S. casualties would’ve diminished substantially using this approach, however, they certainly would not have been zero. And Japanese civilian casualties would’ve sky-rocketed, both from direct violence and starvation.

With the exception of those suffering after the fact from radiation poisoning (little was understood by many involved about this or other aftereffects at the time), the atomic bombs could certainly be argued to have been more humane.

Yes, I just called an atomic bomb relatively humane. In a horrifying war with sixty million casualties, where nothing was truly humane, such comparisons are valid.

Why no surrender?

Though we’ll never know the true thought process behind emperor Hirohito’s eventual decision to surrender, there were any number of compelling reasons–many of which had hitherto been ignored. The Imperial Navy had been eviscerated, the merchant navy that Japan relied upon for vital imports lay largely at the bottom of the ocean, and a once skilled pilot corps was a skeleton of its former self.

Further, a ridiculous number of Japanese cities, whose poorer sections were almost entirely constructed from wood, had been razed to the ground by fire-bombings. To say the population was war-weary is the understatement of the century.

None of these factors had induced the desired effect.

It was consequently decided that Japan, with its leaders hip-deep in a death-before-dishonor-cult, needed a psychological shock so severe that it would have to face reality and end the suffering of all involved.

So we bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Did it work?

Whether these massive explosions (which weren’t actually witnessed by those with the power to surrender); Russia’s declaration of war and wildly successful attack on Japan’s forces in Manchuria; or the popular mood, was the ultimate reason for Hirohito’s change of heart is open for debate. I’d propose that it was a combination that finally generated the required reality check.

Even then, there was a nearly successful coup to prevent the surrender. God emperor or no, that was the state of some military egos.

Political suicide

Though fear of a nuclear Armageddon, plus a healthy dose of hindsight, has affected people’s feelings about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, at the time, they were absolute no-brainers. There simply weren’t a lot of naysayers.

Imagine the fate of any president who revealed after a long, drawn out bloody invasion or blockade that they had refused on moral grounds to employ a weapon that might’ve ended the war far sooner with far less blood. Explain that to the families of dead servicemen. Impeachment? Try hanging for treason.

The American people were also war-weary. No one at home wanted to see the name of another family member, neighbor, or acquaintance appear on the daily KIA list. Said list had lengthened dramatically in ’44 and ’45 as more allied troops became actively engaged in the conflict.

And you can bet your bottom dollar that there wasn’t a single damn allied soldier, pilot, or sailor that had any desire to die invading or blockading Japan. They were overjoyed, if a bit overawed at the news of the bombings.

It’s all well and good to sit here in a 21st century ivory tower and bemoan the decisions of the past. Do you think you would’ve spared Hiroshima or Nagasaki at the cost of dozens of family members, friends, and neighbors, not to mention your own life? I sincerely doubt it.

In the end, the atomic bombings were viewed as a way to avoid more allied casualties, to reduce Japanese casualties, and put a stop to a seemingly endless war against a beaten enemy that had hitherto refused to surrender. No other decision was possible.

One final point. For those that question the U.S.’s morality and humanity, one need only study the post-war occupation of both Japan and Germany by the western allies. We were the good guys.

P.S. Japan in the best light

There is certainly a lot to like about Japan and its people. My personal dealings with Japanese in America have been more than enjoyable. The progression from a feudal society to a major industrial power in less than a century is one of the great achievements in human history. The treatment of their prisoners in the Russo-Japanese and first world wars was renowned for its humanity.

My father who fought against Japan in the Pacific was stationed there in the early 60’s. He had every reason to loathe them, yet found a surrogate family that he became very fond of. I’ve no issue with Japan as presently constituted.

But that does not change what happened in world war two and the preemptive lesson of that conflict–don’t let a cult take hold of the reins of power and expect nothing bad to happen. Acknowledging the reality of what actually happened might possibly be a good thing for the collective Japanese soul.

P.S.S Not a huge fan

If I’m being perfectly honest, and lest you brand me as a complete savage, the targeting of cities for destruction by air in the second world war to “undermine the will of the people”, nuclear or not, has always seemed to me “not what American’s do”. Jimmy Doolittle, a personal hero, thought so as well, and protested twice before the bombing of Dresden. Orders are orders.

Obviously I’m being (somewhat deliberately) naive. Once the dogs of war are off the leash, nothing good happens. I wasn’t there, I didn’t experience the war, and absolutely think that the decision to drop the atomic bombs was correct given the circumstances. Given my father’s anticipated participation, I might not even be here if they hadn’t been dropped.

But I can question the efficacy of targeting cities and civilians, even if Japan’s industry was said to be “cottage” and spread throughout its metropolitan areas. Despite massive destruction, Germany didn’t give up until we finally reduced their fuel production to a trickle.

China and England never surrendered due to bombing. Japan didn’t surrender until after Russia declared war despite horrific damage to its cities, including Hiroshima and Nagasaki. There is reason for debate. Let’s hope there are no future examples that further fuel the discussion.